US businesses lose $300 billion annually in stolen trade secrets; employees can steal thousands of documents with the push of a button; and the FBI acknowledges it cannot stop this hemorrhage on its own. In response, Congress just enacted the Defend Trade Secrets Act (DTSA) to give private litigants powerful new tools to combat this problem.

What’s the import of these tools in practical terms?

Federal court options: the game changer

DTSA gives potential plaintiffs (but only plaintiffs) access to federal courts. Thus, businesses seeking to enforce trade secrets will now automatically have a choice of forums: state court or federal court. Apart from the enhanced remedies available under DTSA, there will often (but not always) be reasons to select federal court: the single-judge docket system in federal court; the law clerks available to federal court judges for cases that are brief-intensive; and uniform rules of procedure and evidence for a business policing trade secrets from coast to coast.

This entry to federal court will permit more than trade secret claims: employee non-competition and non-solicitation cases – generally the province of state court – may be eligible for supplemental federal jurisdiction. This is especially significant in jurisdictions where state and federal courts interpret state law at variance. For example, in California, federal courts more readily enforce restrictions against soliciting employees than state courts there. Similarly, in Illinois, federal courts have been reluctant to adopt the Illinois Appellate Court’s holding in Fifield v. Premier Dealer Services, Inc. 2013 IL App (1st) 120327 that requires consideration other than employment to support a non-competition or customer non-solicitation restriction. (See our coverage of this case here.)

This opportunistic use of supplemental jurisdiction also works in other ways. For example, DTSA does not permit injunctions based solely on “inevitable disclosure.” Yet, many states do. Inclusion of such state law trade secret claims permits achieving in federal court what DTSA alone will not permit for such “inevitable disclosure” cases.

Remedies: new and old

DTSA adds a remedial innovation; it allows private parties to seek a court order instructing law enforcement officials to seize stolen trade secrets and to obtain such orders ex parte: i.e., without notice to or allowing the purported thief an opportunity to appear in court.

This is a powerful remedy, likely aimed at the most egregious theft, like the trading code worth $500 million recently stolen by a financial institution’s employee, the design system specifications worth $50 million recently stolen by a manufacturing company’s employee, or the organic light-emitting diode chemical process worth $400 million recently stolen by a chemical company’s employee.

Seizure is not for everyday cases but for “extraordinary circumstances.” Indeed, the threshold for such ex parte orders is purposefully high: (1) the plaintiff must show the defendant would not comply with an ordinary injunction and (2) the plaintiff must show imminent irreparable harm, among other elements. Even if granted, where a seizure proves to be “wrongful or excessive,” the defendant can countersue for damages caused by the seizure.

Aside from ex parte seizure, DTSA’s remedies adopt the remedies available under the Uniform Trade Secrets Act (UTSA). Like UTSA, DTSA provides for injunctive relief (although not for cases of inevitable disclosure); damages caused by misappropriation as well as alternative options for royalties or unjust enrichment caused by the misappropriation; and both exemplary (double) damages and attorney’s fees for willful and malicious misappropriation.

Defining trade secrets: status quo

DTSA still defines a “trade secret” the same way as UTSA: it is information that (a) is the subject of reasonable efforts to maintain its secrecy and (b) derives independent economic value because it is kept secret from those that could profit from it.

As a refresher:

This continuity in definition may be especially significant with respect to patent-related information. While patent claims require a plaintiff to demonstrate it uses the invention in question, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit holds that is not so for trade secret claims, at least in the international trade context. TianRui, supra. Further, trade secret cases also have a broad jurisdictional reach and can enjoin importation of products made with misappropriated trade secrets, even if the misappropriation occurred outside the US. Id. at 1324. With DTSA’s automatic option for federal court and for ex parte seizure of their trade secrets, trade secret claims will supplement (and perhaps may supplant in some instances) patent claims for that category of cases.

Notice provisions: why care?

To be eligible for exemplary damages (a statutory doubling of damages awarded) or attorneys’ fees in connection with a suit for theft of trade secrets, employers must include language to the following effect in any contract with any employee or consultant regarding confidentiality or trade secrets:

An individual shall not be held criminally or civilly liable under any Federal or State trade secret law for the disclosure of a trade secret that—

(A) is made—

(i) in confidence to a Federal, State, or local government official, either directly or indirectly, or to an attorney; and

(ii) solely for the purpose of reporting or investigating a suspected violation of law; or

(B) is made in a complaint or other document filed in a lawsuit or other proceeding, if such filing is made under seal.

Such disclosures are automatically protected under DTSA regardless of whether this clause is included. Further, this language parallels enforcement policies concerning potential whistleblowers that the SEC, EEOC, NLRB and FINRA have already been emphasizing. As suggested in an alert last year, businesses should already be including language like the following in their non-disclosure, proprietary information, severance and other agreements with their employees and consultants: “nothing in this agreement will limit [employee’s/consultant’s] ability to provide truthful information to any government agency regarding potentially unlawful conduct.” That perhaps deserves to be expanded with this DTSA language but what if it isn’t?

With DTSA and UTSA both providing identical remedies and no pre-emption under DTSA, there are issues to be resolved in future litigation on the integration of both state and federal statutes. For example, envision an employer who failed to include this whistleblower notice: isn’t that employer nonetheless entitled (if the misappropriation was willful and malicious) to claim exemplary damages and attorney’s fees under state law even though barred from seeking such damages under DTSA?

Conclusion: the never-ending story…

DTSA is the beginning of more legislation on trade secrets, not the end. DTSA mandates that the US Attorney General deliver in one year a report to the judiciary committees of the House and Senate with further recommendations to improve trade secret protection. Meanwhile, concurrent with DTSA, the European Union has just adopted its own Trade Secrets Directive, with a definition of trade secrets that is virtually identical to the definitions in DTSA and UTSA.

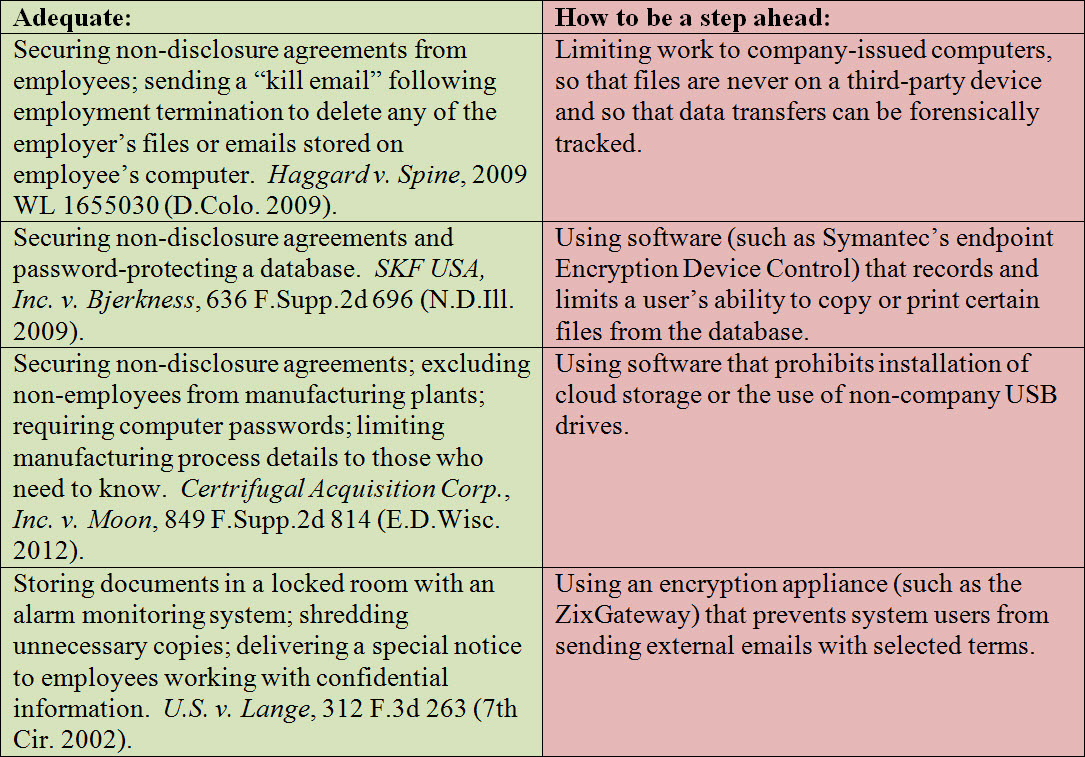

Since both sides of the Atlantic now agree trade secrets are safe only where employers have made reasonable efforts to protect that information, perhaps you should put this alert down and check to see how well your business is protecting its trade secrets. Here are some benchmarks to understand what’s adequate for now, and what may be required in the not-too-distant future, given the pace of technology:

See our alert on ramifications of the DTSA for IPT companies here.